I have no problem with Ben’s theory since it fits the circumstances. But if this is what happened, it started me thinking about how organizations react to disasters. I mean big disasters. Like the space shuttle blowing up, aspirin killing people, or phones setting people’s houses on fire. Because how you bounce back from a disaster is ultimately what makes or breaks an organization.

NASA’s Challenger Disaster

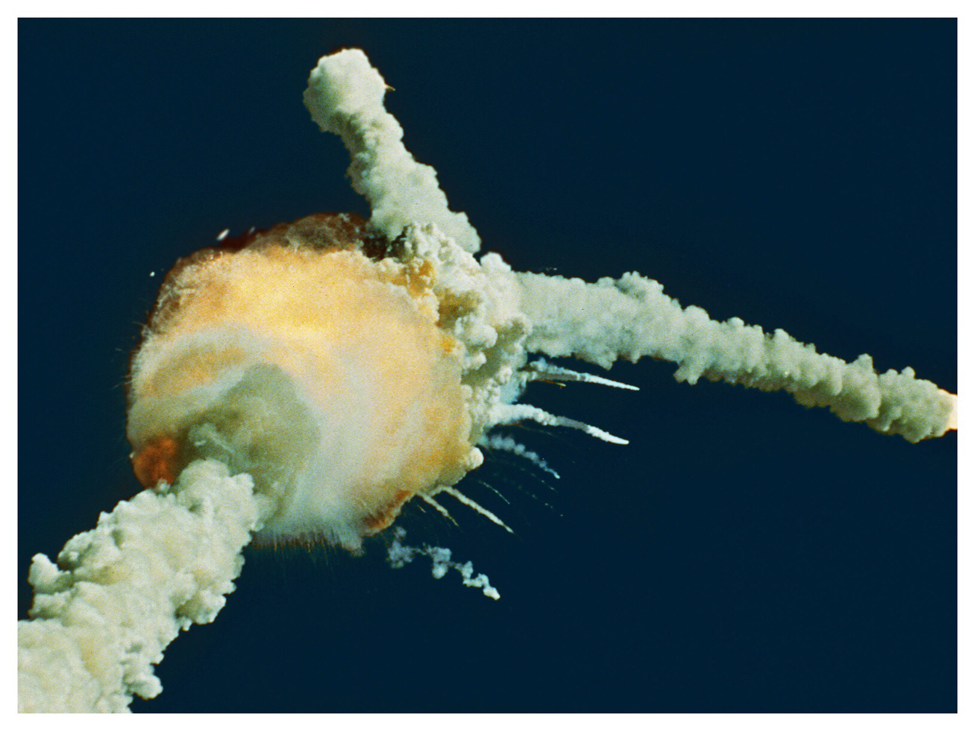

I was fifteen years old when the Space Shuttle Challenger exploded on TV before my eyes. It’s one of those events that I’ll always remember exactly what I was doing when it happened. I was home sick from school that day, and I was so glad to have something other than typical daytime television to watch. I had always idealized astronauts, and it was the first time I’d seen such a disaster like this in real time.

Five years later, I was working for NASA as a co-op student at Stennis Space Center in college from 1991 to 1993. For any of you NASA people, I was at the Financial Management Division which was run by Ron Carter at the time. I’ll never forget chatting with engineers who were directly involved with the shuttle engine program. They described to me how NASA had over corrected after the Challenger disaster. There were layers upon layers of new reviews, development of everything slowed to a crawl, and everyone became gun-shy regarding trying anything with even the smallest risk. NASA had lost some of their creative mojo after that accident and struggled to get it back.

It also gave ammo to the anti-human camp. Anyone working for NASA quickly becomes aware of an internal battle that rages to this day. Transporting humans versus data. There are those who think that transporting humans through space is frivolous when you take into account the complexity and cost that it adds to any space mission. Every gram on that rocket ship is precious. To “waste” that budget of grams on food, clothing, and life support when you could be transporting cameras and sensor equipment is a big tradeoff. And spending money on transporting humans meant that other worthy projects went unfunded.

Transporting people also had the huge limitation of sticking to what is essentially our own backyard. You can’t send people to Pluto. But you can send a probe. Without people on board you can travel farther, carry more, and spend less. Working at NASA and listening to the two camps battle this out and make their case influenced how I see tech today. It’s one of the reasons why I divide the tech world into those who move pounds versus those who move information. I see moving information as the higher calling. Ultimately organizations that specialize in moving pounds are simply building better wagons. Moving information is more consequential, more efficient, and more effective. But I digress.

If the Mac Pro Was a Financial Debacle, Apple Must Resist Overcorrecting

Back to Apple. If the Mac Pro was some kind of financial blow up, Tim Cook needs to be careful that they don’t overcorrect. The knee jerk reaction is going to be to analyze every new idea to death and shy away from trying similar new projects. He needs to be the steady hand that helps Apple to find the middle ground. Apple needs to do their due diligence but not get left behind because of too many layers of reviews and sign-offs.

Apple has taken some criticism lately for appearing to move slowly when it comes to updating their products. I’m not sure if this is warranted or not, because unlike other companies Apple doesn’t broadcast every little thing that they do behind the scenes. I just hope some sort of financial PTSD triggered by the Mac Pro isn’t the cause. I’ve seen from the inside what financial disasters can do to a company, and it’s not pretty. Overcorrecting is the path of least resistance, and Tim Cook needs to be sure that doesn’t happen.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed