Why the controversy? Different parts of the company view it from different angles. A liberal return policy is always advocated by the sales and marketing groups who are trying to reach out to new markets. They see it as a way to reach new customers who will buy give the assurance that they can always change their mind later.

A stricter policy is always being pushed by the operation type groups that have to deal with all the returned product. In their eyes, they see mountains of returned products as a monumental waste where most of the product was not defective but returned by customers who purchased on a whim. They would think that Apple would be better off if these fickle customers had not purchased that iPad or iPhone in the first place. Now Apple has to deal with returned components it cannot sell as new.

Basically, it’s easy to quantify the costs that a company absorbs on their income statement to support a given return policy. The benefits however, not so much.

Lets say that you are thinking about upgrading to the new iPhone 7 but aren’t sure if it’s really worth upgrading from your current 6s . So you order one and decide to try it out for a couple of weeks. But after that two or three weeks you decide you’ll just stick with your current iPhone and send the new one back. What happens?

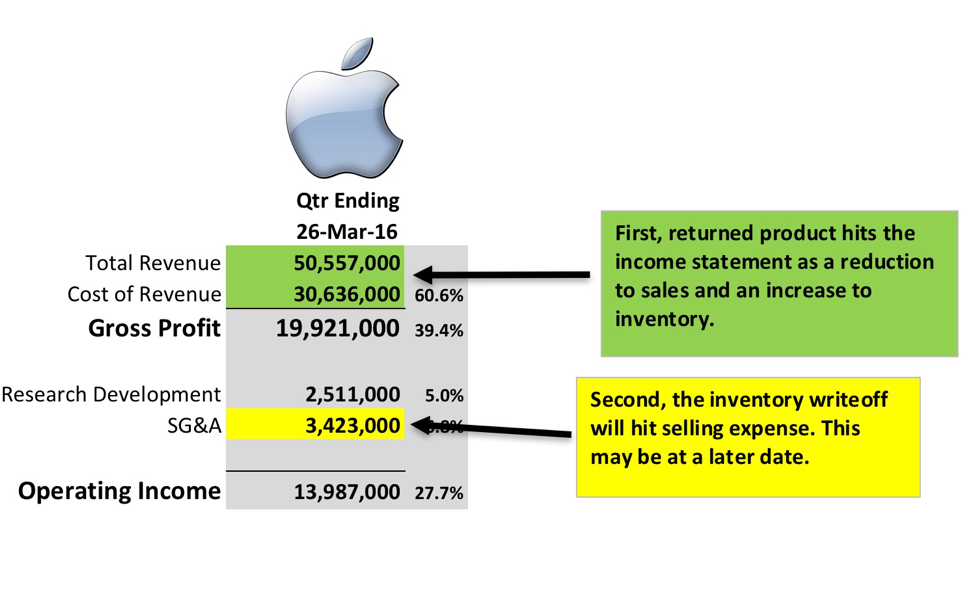

First, Apple takes an immediate hit to their sales and gross margin for reversing the original sale. It’ll show up in the income statement as a reduction to sales and cost of sales. So what was once a high gross margin sale is now a high gross margin torpedo. This part everyone kind of understands.

Is this cost worth it? That’s the million dollar question. Whereas, the operations group can point to the high cost of the return policy with great precision, the sales group can’t easily quantify the benefits. They have to rely on making the case that it’s the right thing to do in the name of customer satisfaction. But even this argument will start to crumble if returns ever start to reach alarming rates. All policies are in place so long as they are on the right side of the cost-benefit equation.

Apple’s current policy is tenable mainly because the number of people who abuse it remain at a low level. The losses that Apple suffers from them can be spread among all of Apple’s products at a small surcharge to everyone else. When Apple’s pricing analysts price new products they will always attach an assumed return rate. So returns aren’t free. It’s built into the price. The more that people will take advantage of the policy, the higher that upfront device costs will necessarily be.

But if this small group of serial abusers starts evangelizing that Apple encourages a try-before-you-buy policy, problems may lie ahead. If return rates go up, especially in an environment when sales are flat, this issue will come to the forefront. It’s in the standard corporate financial playbook to revisit your return policy when your financials take a turn for the worse. Apple is in no means in any financial trouble, but they aren’t growing like they were only a couple of years ago.

It’s not that Apple doesn’t want people to try their products. The problem lies in whether or not other customers are willing to bear these costs. At $650 - $950 for an iPhone, Apple is already at the top of the pricing pyramid for smartphones. With new handsets coming from other manufacturers with materials and components that nearly match Apple’s iPhone, for around $400-$500, the heat will be on Apple very soon.

The last thing that Apple wants to see is this group of serial returners growing. Most other retailers have already had to clamp down on this group with establishing refunds only for defective merchandise, imposing restocking fees, or limits on specific problem customers. Will Apple follow suit? As usual, that decision will be made by the customers.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed