Why is this a problem? In a nutshell, because only the standard costs of the vehicle are put into inventory. So any costs above the standard flow directly to the income statement in the current period. This means costs are recognized immediately but the revenue is recognized in a future period. There is no “match”.

Basic GAAP accounting tries to prevent this situation from ever happening by forcing companies to capitalize their inventory. It tells them to set up standards for material, labor, and overhead and, as they finish units, to put these new units into inventory at the proper standards. Then, even if they sell this inventory a year later, the cost of the inventory gets matched to the sale. Normally, this process works fairly well, and any variances from these standards are a small percentage of the cost of goods sold.

But here is where Tesla’s situation gets interesting. At the end of 2017, when Tesla was setting up the 2018 standard costs for the Model 3, they would have used pie-in-the-sky volume assumptions. In November of 2017 at the Q3 earnings–release conference call, Musk stated that Tesla should be at a production rate of 5,000 cars per week by the end of Q1 2018 and that it wouldn’t be very difficult to get to a rate of 10,000 cars per week with almost no capital required shortly thereafter.

Tesla’s purchasing group would have used these lofty volume assumptions when estimating per-part material standards. But if Tesla never hits these volume targets, that means they pay a higher price per part than what they were expecting. A similar situation occurs with overhead. If you spread plant overhead and depreciation over 5,000 units per week instead of the 10,000 you were expecting, that means your standard is only capturing half of the real costs.

So, as I mentioned earlier, the concept of inventory is that you match your cost of production with your sales revenue. But only the standard costs get put into inventory. But what about all of those material and overhead costs that were not captured in the standard cost? Those unfavorable variances are immediately recognized in cost of goods sold as manufacturing variances. They are not inventoried.

In the fourth quarter, Tesla could end up in a situation where their gross margins are materially misstated because of incorrect standard costs. This means that they will be selling cars but only matching a portion of the true cost. I say a portion because all of the costs over standard would have hit the income statement in the second or third quarter depending on when the cars were built.

Now, no one outside of Tesla knows if this is what is happening. In a perfect world, as Tesla catches wind that their volume estimates were wildly optimistic, they would correct their standard costs. Each month they should evaluate if a bad standard rate is going to cause a material misstatement on the income statement.

For most companies, setting standards is a once-per-year activity. Doing mid-year corrections is fairly unusual and only done only when egregious errors are found. If the impact is large enough, the accounting chiefs would need to explain to company management why they are impacting the income statement with these mid-year standard cost corrections and what the impact will be on current and future financial statements.

But what gives me pause with Tesla is that the accounting chiefs who would normally explain all of this to Musk or possibly get his approval to make changes have left the company. Could there be a connection?

Of course, any favorable bump in gross margins in the 4th quarter would be short lived. This favorable tail wind only exists while they are selling previously built inventory. Eventually they would either match production with sales or correct their standard costs to account for their true costs.

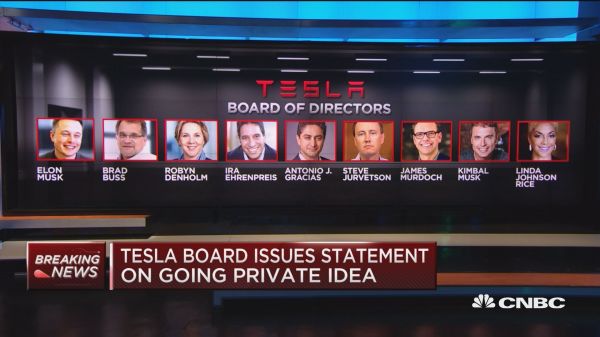

But for an unscrupulous CEO who desperately needs to raise capital, one quarter of positive margin movement may be all he needs. This however, is exactly the kind of misbehavior that GAAP accounting is trying to prevent. It is encumbent on the board of directors, to whom the outside auditors report, to ensure that quarterly financials are not tinkered with to manipulate the true picture of financial health.

There may not be a lot that the Tesla board of directors may be able to do with unseating Elon Musk. But I would argue that they don’t need to go that far with restoring their reputation. If they take an active role in the financial audits via their hired auditors to ensure that everything is on the up-and-up, that would be enough. Is inventory getting correctly valued? Do material standards reflect the true prices with current unit volumes? Is depreciation getting allocated using the 5,000 unit/week rate versus the planned 10,000/week? Are the 420,000 reservations a legitimate number?

If Tesla’s board can get out in front of any potential issues this would go a long way towards restoring their reputation. They need to give the auditors the message that they have the boards full support and that they can go anywhere they need to go without fear of losing the account. And further, they should solicit feedback from investors on any areas of concern that may exist and pass this along to the auditors. Later, if possible, they need to promote with investors what was discovered and allay any concerns over reservation counting, inventory valuations, COGS vs SG&A classifying, etc. If Musk knows that the board is watching and willing to set the record straight, he will be much less likely to throw out bombs that aren’t “factually challenged”.

If word gets out to the investors that Musk was playing games with the figures the board won’t need to justify getting rid of Musk. The investors will be demanding it. Tesla shareholders value Musk’s grand vision and will give him a lot of leeway. But one thing they won’t tolerate is any kind of funny business with their financial statements.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed